She Helped Me Become the Person and Clinician I am Today: A Mother’s Day Tribute

Mother’s Day is a time to honor not only our moms, but also the mother figures who have helped shape us. In that spirit, I’d like to share the story of someone extraordinary who helped make me the person and clinician I am today, and who continues to impact how I care for older patients at Patina.

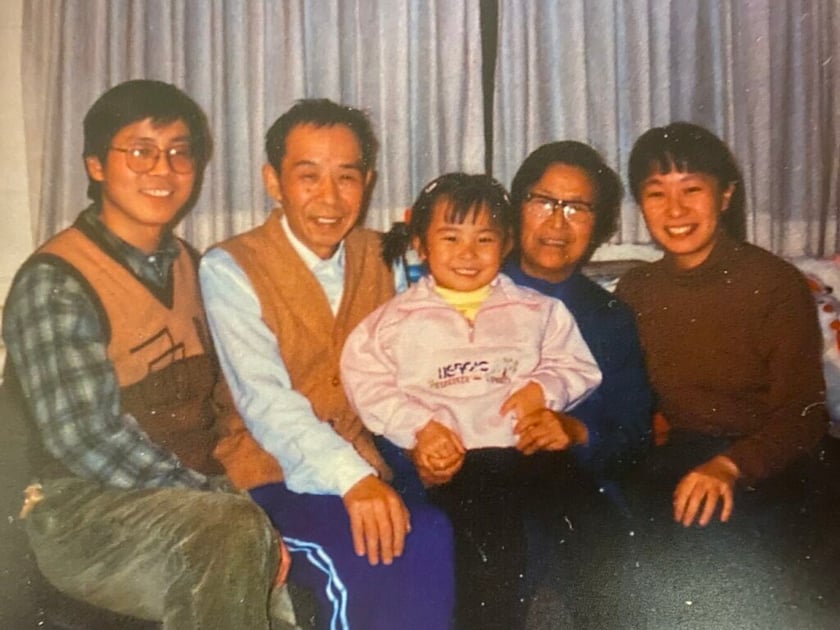

I called her Wai Puo (“why-poowuh”) which is “grandma” in Mandarin. My given name is Yue, and so she called me Yue Yue. The Chinese character means to reach over, which is a bit of a metaphor, because when I was born my parents already knew they’d be going to America, and that I’d be part of that journey.

To explain: My dad was accepted into graduate school in Ohio around the same time my mom learned she was pregnant, so they and my grandparents decided to raise me in Shanghai until my parents could finish their programs. My grandparents became my primary parental figures until I was four.

My grandma was the family matriarch, and she ran the show, even with my grandpa. She wasn’t loud, but she was firm. When she spoke, no one would push back.

My grandma was very principled, very much black and white about what’s wrong and right, very resourceful, and also very frugal. She raised three kids, and then each of her grandkids. She’d express her love through an abundance of food — handmade dumplings, pressed pancakes, hand cut fruit. When she cooked, she was very heavy handed with the garlic. Even as a toddler, I still remember the smell and the vision of her crouched in our living room on one of my kiddie stools, pounding her mortar and pestle for the entirety of an 30 minute episode of one of my cartoons until the garlic was smashed to a paste-like consistency to her liking.

With my dad’s graduation on the horizon, my grandparents moved to Ohio in their mid-sixties without speaking a word of English, so I could transition to live with my parents. After a year, they left, and I’d see them every summer when I visited Shanghai. In those summers I became a bit of a troublemaker, because I’d challenge my grandmother. Nobody in my family dared to do that. But we grew a lot closer through my incessant questioning oftentimes with the simple syllable and word: “Why?” or “Wei Shen Me?” in Chinese. She called me her littlest daughter.

In honor of Mother’s Day this year, I want to celebrate my grandmother, Gao Jian Hui. In life, she was brave, strong-willed and principled. She was my first female role model, and even though she lived into her late eighties, I never saw her as “old” or any of the stereotypes that usually accompany aging. My grandma aged beautifully.

And while her life had a profound impact on me personally, it also impacted me professionally, largely because of her experience with healthcare in her final months. It influenced my career decisions and clinical practice, and it is why I feel so strongly at Patina about helping our patients understand their values and goals, their medical situation, and ensuring that each person’s priorities are heard and respected.

Here is how that unfolded.

In 2017, my grandmother started experiencing spontaneous fractures, likely as a result of a cancer that she had been treated for almost 20 years earlier.

In Chinese culture, there’s a belief in positive thinking, sometimes to the point where people won’t share news about their own health because they believe you’ll be better off not knowing. This happened with my grandma, and it was really hard – especially for someone accustomed to being in control of almost everything.

My grandma spent her last six months hospitalized. My family had the best intentions – visiting everyday, showing love through acts of service like bathing her and feeding her. Yet, she wasn’t able to leave her bed, let alone the hospital, due to the pain and risk of another fracture. She desperately wanted to know why. No one told her.

Toward the end, my family struggled with really hard decisions regarding life-sustaining treatments for her. Oftentimes, these decisions are made in haste or they’re not made at all, and we default to the status-quo.

And in my grandma’s case, this meant having a feeding tube placed. Yet, being who she was, she made her wishes clearly known by ripping it out, repeatedly.

As her health deteriorated, I flew to Shanghai to be with her and my family. We were in the same situation as many other families, clinging to the hope that science could cure our current predicament. We slowly processed that we were witnessing the limits of modern medicine, and recognized the implications of these decisions – especially how my grandma wouldn’t have wanted the feeding tube if she had only known that her condition wasn’t reversible.

In her last week, my family rotated so there was always someone at her bedside. I was no longer juggling roles as a clinician and a family member. I could simply be her Yue Yue, and do my best to help carry her with the same love and care she had carried me.

She and I were alone on her last night. I held her hand and watched as the space between each of her breaths grew longer and longer. I also noted the time, knowing that the morning would bring new family members to sit.

Five minutes before they were due, her breathing stopped, and passed peacefully.

In her last few breaths, I like to think that she left this world on her own terms. It was quiet. She was holding the hand of someone she loved, and she knew how much we loved her. I also like to think she knew I was doing my best to let her run the show, which meant just being with her and holding her hand as she reached over to the other side.